Exemplary Teaching Award in General Education 2023

This year, eight teachers were nominated for the Exemplary Teaching Award in General Education and the awards go to:

- Professor James D. Frankel of the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies

- Dr. Han Dongkun of the Department of Mechanical and Automation Engineering

- Professor Hayden Kee of the Department of Philosophy

The Exemplary Teaching Award Ceremony

Date: 26 June 2024 (Wednesday)

Time: 10:30 a.m. – 12:15 p.m.

Venue: LT6, Yasumoto International Academic Park (YIA), CUHK

All staff and students are welcome.

Professor James D. Frankel

A native New Yorker, James D. Frankel holds degrees in East Asian Studies and Religion from Columbia University. His expertise is in the history of Islam in China, with scholarly interests in the comparative history of ideas, and religious and cultural synthesis, as highlighted in his books, Rectifying God’s Name: Liu Zhi’s Translation of Monotheism and Islamic Ritual Law in Neo-Confucian China (University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2011) and Islam in China (I.B. Tauris, 2021). He has lived in China and traveled extensively in Asia, Europe, and North America where his research has included work with scholars and religious leaders of diverse communities. He is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, where he is also the Director of the Centre for the Study of Islamic Culture.

As a scholar of religion, I count some of the greatest teachers in human history as role models. They have all exemplified a profound sensitivity to the needs, interests, mentalities, and personalities of students while trying to impart knowledge. My intuitive tendency is to try to reach students in whatever condition I encounter them. The job of a teacher is not to instill ideas per se, but to facilitate students’ own discovery of truth, bringing their moral and intellectual instincts to the conscious fore. When a teacher’s enthusiasm is obvious, most students will feel naturally drawn to join in the process of learning. Then ideas begin to take hold, sparking a quest for greater and deeper understanding in the expanding mindscape.

I endeavor to provide students the broadest possible perspective on the world around them. I want them to grasp big ideas, including reflection on what it means to be human. As a lover of words, I remind my students that the etymology of “university” derives from “universe”, and thus each class they take is devoted to a particular aspect of the totality of knowledge. By helping them acquire knowledge, and apply it to their lived experience, I hope they will transform it into wisdom as they grow and embark on their lives beyond the university. The core purpose of General Education at CUHK is to put students in “dialogue” with both the natural world and our shared humanity. I am gratified that the study of world religions is included in the common curriculum because I believe that religion is one of the most transparent windows onto the human condition and a phenomenon that addresses and expresses our place in the cosmos.

In my teaching, I start by identifying the familiar and correlating it with newly introduced ideas. In my discipline, we examine the search for truth in the form of universal principles. My approach, therefore, is to demonstrate the universal through the specific. I emphasize the universality of religious patterns of human belief, behavior, and interaction, even as I seek to provide a thorough, detailed, and objective view of any specific tradition. Alternating between telescopic and microscopic lenses through which to view phenomena, I use examples and case studies, drawn from the richness of the world’s religious traditions to illustrate common elements found across creeds and communities of faith.

I am especially interested in the evolution of religious views and communities in their negotiations with contemporary society, and the manifestation of religious themes and values in popular culture. Every semester, I call my students’ attention to how themes germane to religion appear in current events and the cultural zeitgeist. I encourage students to be aware of their surroundings as they walk through life, to hone their sensitivity. This is why one of their assignments asks them to observe/participate in a religious practice within its traditional context, e.g., a temple, mosque, or church, and to engage with members of the community.

One does not have to be religious to appreciate how religious traditions contain and reflect fundamental, universal principles and values, such as cultivating compassion, striving for justice, honoring the nobility of one’s fellow beings, and respecting the sacredness of nature. In the spirit of general education, these ideas may help shape students into responsible and responsive global citizens.

The challenge of addressing diverse audiences has taught me how to balance cultural and religious sensitivity with the demands of academic rigor in an atmosphere of intellectual honesty and mutual respect. But rigor does not necessitate rigidity. I rely on humor and personal sharing to try to make my classroom a safe, comfortable environment for the free exchange of ideas. Storytelling, so basic to the evolution of our species, is also essential to my pedagogy.

Teaching, mentoring, and close interaction with students have always been the foundation of this profession. Helping to bring students to a better understanding of themselves and inculcating within them a love of learning, with the proviso that they must be active participants in the process, is the heart of my work and the work of my heart.

Dr. Han Dongkun

Dr. Dongkun Han is currently a lecturer at the Department of Mechanical and Automation Engineering, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. He earned his Ph.D. degree at the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering from the University of Hong Kong. He was a research associate at the Department of Informatics, Technical University of Munich, Germany, and was a research fellow at the Department of Aerospace Engineering, the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA. He held visiting academic positions at the Department of Electrical Engineering, German Institute of Science and Technology, Singapore, and at Information Systems Laboratory, Stanford University, USA.

Dr. Han’s educational research interests include Artificial Intelligence technologies in general education; E-learning and hands-on pedagogies in robotics education; and professional development for teaching staffs in engineering. To promote Sustainable Development Goals, Dr. Han co-founded the CUHK Smart Garden, which is a teaching and learning platform to develop renewable energy technologies.

“If we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow. – John Dewey”

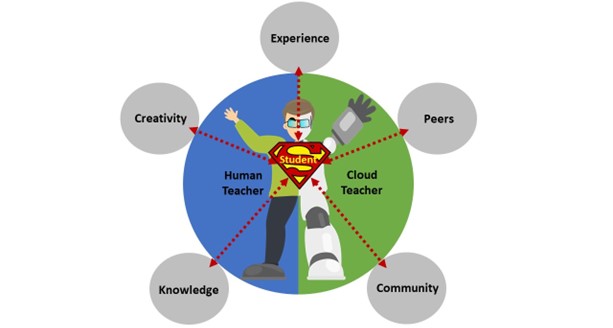

As a teacher in engineering, I firmly believe in a superlative combination of instructor and technology, which enables students to take a more active role in learning, interacting with their peers, and creatively making their contributions to society. A student-centered hybrid teacher system is developed as follows (see Figure 1).

Figure (1)

Human teacher: A real person helps students acquire knowledge and competence effectively and efficiently. S/he could develop or apply various educational technologies and devices to accelerate students’ learning. The role of a teacher can go beyond teaching, such as being a counsellor, mentor, role model, and so on.

Cloud teacher: The instrumental element or educational technologies could be any format of carriers that facilitate teaching and learning, bringing cause-effect results through its implementations in the system. Basic features include: 1) 24/7 functional Q&A service to students; 2) Big data analysis for individualized education (hence, precision education); 3) Accessible and online experiential training; 4) Automatic assessment and invigilation; 5) Intelligent teaching assistance based on robots and AI; and 6) Related software like APPs, websites, micro-modules, or integration with hardware.

Collaboration between human teacher and cloud teacher in a hybrid mode: 1) Human teacher designs and manages cloud teacher; 2) Cloud teacher gives human teacher a better way of teaching and learning in various aspects, like automatic and formative assessments; 3) Cloud teacher is able to establish students’ profiling and helps human teacher in making predictions and course preparation; 4) Cloud teacher analyzes students’ on-the-spot inputs, and provides instant feedback to human teacher, who can give timely interventions to students; 5) Cloud teacher saves time and energy of human teacher such that s/he can perform more effectively; 6) Human teacher fine-tunes cloud teacher based on user experience and feedbacks.

Hybrid Teacher System in General Education

General education is an essential type of education that provides students with a broad and well-rounded knowledge base across various disciplines, rather than focusing solely on specialized or vocational subjects. General education opens another window for students to look at the world and look at themselves. The student-centered hybrid teacher system demonstrates its effectiveness in several general education courses:

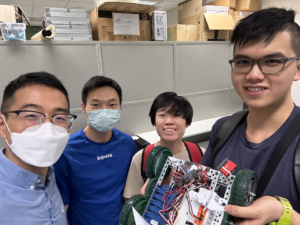

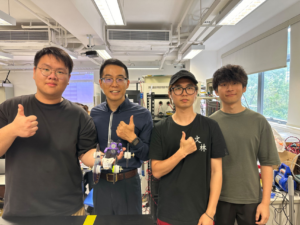

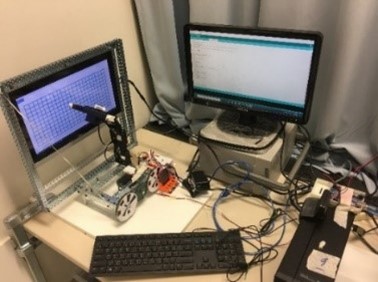

a) Flipped online hands-on training in an unmanned robotic laboratory: A major concern in online/distance engineering education is how to overcome problems associated with laboratory components of the courses. A new eLearning pedagogical approach called flipped online laboratory is proposed for teaching robotics (UGEB2303 Robots in Action). The basic idea is to conduct an online synchronous laboratory (provided by the human teacher) with the help of flipped asynchronous laboratory instructions (micro-modules and remote-control software provided by the cloud teacher) for students to make their first robot. An online robotic laboratory has been constructed based on our robotic laboratory with real robots. (See Figure 2a, b)

|

|

|

| Figure (2a) One set of remote controllable robotic arm with sensors and a touchable drawing panel. | Figure (2b) Ten sets of remote controllable robotic arms in an unmanned robotic online lab. |

b) “Cloud Teacher” for individualized education: We have built a “cloud teacher”, which is a textual-based conversational agent for answering questions from students in Mechanical Engineering via machine learning technologies. The central idea is to train the agent by utilizing open-source artificial intelligence tools from Google’s DeepMind, such that the agent can understand and answer questions raised by students with an acceptable confidence value. Big Data Analytics can be conducted accordingly based on students’ historical questions, and prescribed teaching can be provided. We used this method in general education courses UGEB1407 Demystifying Artificial Intelligence and UGEB2303 Robots in Action.

c) Smart garden teaching and learning platform: Based on the idea of the student-centered hybrid teacher system, a teaching and learning platform has been constructed. The smart garden provides students in the course UGEB1307 Energy and Green Society with a platform for learning renewable energy technology (Knowledge), developing innovative devices (experience and creativity), exchanging ideas with other students (Peers), and displaying their products to the public (Community), with the support of various APPs and software.

Professor Hayden Kee

Hayden Kee received his B.A. in Philosophy at Mount Allison University (Canada), his M.Phil. in Philosophy at K.U. Leuven (Belgium), and his Ph.D. in Philosophy at Fordham University (USA). Kee joined the Department of Philosophy at the Chinese University in 2021.

Kee’s research focuses on questions of mind, language, and cognitive science, all broadly construed. He is interested in how language and other higher cognitive abilities relate to more basic, embodied abilities and processes, such as emotion, perception, action, and preverbal communication. His approach to these questions is based in the European phenomenological tradition, in particular the work of Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty. He also draws from analytic philosophy; 4E cognitive sciences; and empirical research in psychology, linguistics, and neuroscience. His work also engages the Indian philosophical tradition, especially the yoga school.

Kee has been awarded various research fellowships and grants from numerous international funding bodies including the Canadian Research Council, the German Academic Exchange Service, the John Templeton Foundation, and the University Grants Committee of Hong Kong.

My approach to sharing philosophy is inspired by that of Socrates. I believe that philosophical reflection emerges naturally within our everyday lives if our innate human curiosity is cultivated and not suppressed. At the same time, the emergence of philosophy also introduces something of a rupture with our everyday activities and way of life, allowing us to take a critical distance from ourselves, our society, and our values. This distance is of paramount importance if we are to achieve intellectual autonomy: the critical, reflective ability to make our own informed, wise choices concerning our values, our beliefs, and, ultimately, our selves.

Achieving this ultimate goal of philosophy is a lifetime undertaking and a perpetual work in progress. To help students advance towards it, I set several proximate goals for my teaching.

(a) To progress in philosophy, students require attitudes of curiosity and appreciation towards philosophical inquiry. Though I believe a philosophical impulse is innate in all of us, this can easily be snuffed out by surrounding cultural cynicism and an instrumentalist attitude towards education.

(b) Students need to see and feel the relevance of philosophy for their own lives. Great works of philosophy can seem abstract and are often culturally and historically distant. My task is to show students how the texts we read are about the lives we live.

(c) Students need to develop the critical, creative skills and values of philosophical thinking. As these skills involve elements of analytic rigor, practical technique, and artistic inspiration, there is no simple formula for their instruction, and no replacement for practice under the watchful eye of someone more experienced.

The following are some of the techniques I employ to help students advance towards these goals.

(a) Cultivating environments and attitudes for philosophy. To venture a response to a philosophical question is to make oneself intellectually and emotionally vulnerable. To be willing to take that risk, students need a supportive, safe environment for inquiry. I prepare that environment implicitly by showing my own vulnerability, uncertainty, and fallibility in the way I model inquiry and invite discussion. Instead of introducing discussion with “what do you think about…” or “what is Descartes’ view on…”, I begin with “As I was reading, I found myself wondering…” I emphasize that the point of the activity is not only to “get it right,” but to develop skills of inquiry and appreciate different perspectives on an issue. Once students realize that even a misstep can be helpful in philosophical discourse, the anxiety around contributing to class discussions lifts and inquiry can flourish.

(b) Connecting classroom study to student lives. Students do not always immediately see the relevance of philosophy to their lives. If I ask students directly which is more important for the good life, meaning or pleasure, their faces go blank. But when I tell them the story of a close friend who began clawing her way out of clinical depression by rediscovering the sensuous delight of dance, their minds begin to turn. For there is not a student in that classroom who does not either herself suffer from mental illness or know someone who does. Concrete examples like these land with students. Building from them, we make our way to more abstract questions.

(c) Modeling and scaffolding processes, evaluating products. Once students are motivated and provided with a conducive environment, further support is required to help them produce excellent work. To that end, I scaffold major assignments and sequence them into manageable steps. Whenever possible, I deconstruct a daunting term paper into subsequent phases of brainstorming, outlining, drafting, peer review, final submission, and follow-up discussion. Providing low-stakes assignments with thorough feedback along the way also reassures students that they are on track to achieve their course goals. I then evaluate the final product using the clearest grading schema possible and provide detailed written or oral feedback.

Though Socrates is the model and inspiration for my own philosophical teaching, I do not begin the semester with him in introductory classes. I end with him. By the end of the semester, a question students often have, whether or not they have enjoyed the class, is what the point of philosophical reflection is when we seldom arrive at definitive answers to the questions we set ourselves. The point of the questions, Socrates shows us, is not so much the answer, but the way we become who we are through the asking.