通識教育模範教學獎 2014

時間: 3:30pm - 4:45pm

地點: 香港中文大學邵逸夫堂留足展覽廳

2014年度榮獲提名的老師有九位。教務會通識教育委員會議決頒發「通識教育模範教學獎」予日本研究學系的何志明教授,以及人類學系的麥高登教授。

何志明教授

Professor Ho Chi Ming obtained his B.A. in Japanese Studies from The Chinese University of Hong Kong, M.Phil and Ph.D degrees from University of Tsukuba in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. Professor Ho has been teaching in the Department of Japanese Studies since 2003. Professor Ho has taught the General Education course UGEC1281 Understanding Japanese Language and Culture over the years. His publications include: 《從日語看日本文化》 (Understanding Japanese Culture through Japanese Language), 《日本文化60 詞》 (60 Keywords of Japanese Culture), 《現代日本語における複合動詞の組み合わせ-日本語教育の観点から-》 (A Study on the Combination of Compound Verbs in Contemporary Japanese from the Perspective of Japanese Language Education).

I am honored to receive the Exemplary Teaching Award in General Education. This award not only recognizes my past efforts, it also brings me great encouragement and confidence to continue pursuing my future endeavors in teaching.

As a language specialist, one of my primary roles when I teach in a class is to act as a facilitator, guiding students to better understand Japanese culture, tradition and society through discussions and exchange of thoughts which help students develop their own important analysis about the topics and issues in both old-time and contemporary Japan. In addition to textual materials, I believe it is important for the students to have direct access to Japan’s mass media platforms, including the visual aspect as well, so that they may experience and develop their own interest-driven ideas of what Japan is. The main points of my teaching philosophy are summarized as follows:

- encouraging interest-driven motivation of the students as such that they can interpret Japanese culture and traditions through exposure to materials in their native language form, given that grammar and texts usually produce nuances that are important in Japan’s unspoken ways of communication. It is important to convey to our students the message that “knowing others’ culture means knowing more about ourselves”;

- encouraging the students to think critically and comment on the characteristics of Japanese culture and develop their own comparative analyses of cross-cultural understanding by both Japanese and Hong Kong speakers; and

- encouraging the students to apply what they have learnt from the course materials to different scenarios and make their own judgments in various contexts and scenarios. My role as the course facilitator is to train the students to understand the complex nuances of culture through communication in the human society and the world around us.

I aim at generating enthusiasm for learning among my students by going through current affair topics from the Japanese media which mimic the daily information consumption of Japanese people. Through the use of selected news video clips from various news broadcasters in Japan and documentary relevant to the course syllabus (with Chinese subtitles provided by my colleagues and myself), a platform conducive to interaction and analytical discussion among my students will be built up. Case studies incorporating ideas from students in the class are then designed to provide opportunities for critical thinking. The prime objective of incorporating ideas from the class is to encourage those students who are comparatively passive in speaking in the native language to vocalize more about their opinions in class. Meanwhile, the writing part shall provide a channel for all to express their own views in the textual form. The essays which I review are then utilized for further discussions on the relevant topics. Critical thinking and opinion formation are not restricted only to verbal exchanges but also in the term-end research paper which is a venue for critical thinking and creativity supported by references and research. Through open and free discussion, my objective is to dispel “Japanese culture and society stereotypes” and allow students in the class to assume an active role in conceptualizing what “Japaneseness” and “Japan” are, and then to adopt comparative perspectives to analyze how they are different from our own culture and society. Pre-conceived ideas are now challenged constantly through different perspectives.

Last but not the least, the incorporation of research findings in my teaching is one of the most significant elements which provides a platform for me to share with my students the latest research outcomes in order to enhance their understanding of certain relevant topics in the course. For example, issues from research findings related to intercultural communication between people in Japan and Hong Kong are introduced as lecture materials.

My academic publication titled 《從日語看日本文化》 (Understanding Japanese Culture through Japanese Language) published in 2010 is specially written for my course and it is one of the five books in the current General Education series jointly published by the CUHK Office of University General Education and the Chinese University Press. This book has been used for a few years since it is first published and I believe that it caters to the learning needs of students taking my course.

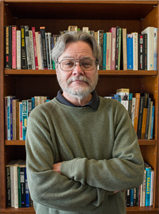

麥高登教授

Professor Gordon Mathews has been teaching in the Department of Anthropology at The Chinese University of Hong Kong for the past twenty-one years, and is now chairperson of the Department. Professor Mathews has written books such as What Makes Life Worth Living? How Japanese and Americans Make Sense of Their Lives (1996), Global Culture/Individual Identity: Searching for Home in the Cultural Supermarket (2000) and Chungking Mansions: Ghetto at the Center of the World (2011), which, in its Chinese translation, won the 7th Hong Kong Book Prize. Professor Mathews has edited and co-authored books on topics ranging from Hong Kong identity to the Japanese generation gap to the cross-cultural pursuit of happiness. Professor Mathews is President-elect of the Society for East Asian Anthropology, American Anthropological Association, co-editor of Asian Anthropology, and Organizing Committee member for the World Council of Anthropological Associations.

I love the subjects I teach. I believe that if my students can understand these subjects, their understanding of the world and of their own future lives will be greater. I teach three General Education classes, UGED2980 Meanings of Life, UGEC2990 Globalization and Culture and UGEC1681 Humans and Culture. I have designed these courses with my own undergraduate experience at Yale University in mind—what are the courses that might have taught me most about the world that I never had the chance to take? In all three of these courses, I use my own books, as well as many other books, as class readings, not because I think they are particularly good, but simply so that students can better understand how I think, and can respond. Students who can effectively criticize my books in their essays written for my classes often get A’s.

One key element of my teaching is class discussion. I never lecture for more than twenty minutes at a time. Interspersed with this lecturing, I offer classroom discussion questions, questions dealing with issues relating to the lecture and readings. For example, in a class on globalization and mass media, I might ask, “If you were the ruler of a poor country, would you block the internet? Why? Why not?” In a lecture on culture and gender, I might ask, “Why do some men like to look at pictures of unclothed women, but most women don’t like to look at pictures of unclothed men?” In a class on meanings of life in religion, I might ask, “Would the world be better if we all believed in God? Or would it be better if we all didn’t believe in God?” In a lecture on contemporary cultural identity, I might ask, “Do you love your country?” first to Mainland Chinese, then to Japanese, then to Americans, and finally to Hong Kong students in the class, to get a debate started. Then I might ask, “Should people love their country? Why? Why not?”

In these discussions, I am very careful not to provide any “answers”: the purpose of these questions is to get students to think for themselves. I don’t ask students to raise their hands if they want to speak—I simply call on students who look at me. I later ask some of these questions in my take-home midterm and final examinations. Class discussion thus forms an essential part of class learning and teaching. Students do need to learn facts, and I am careful to teach a framework of factual knowledge. But most important is that students learn to think for themselves on the basis of facts. I don’t want to teach students to hold a particular opinion but rather to be able to think clearly, logically, imaginatively, and fearlessly in arriving at their own opinion, whatever that opinion may be.

|

Underlying all this is the deep affection I feel for students. These students remind me of myself forty years ago, and I have a sacred obligation to teach in the best and most innovative way that I can. I often emphasize to students that although I must grade them, grades don’t matter—what matters is their own effort to think for themselves. I say, “Of course I’d prefer you to do well. But at the same time, remember: really stupid people sometimes get A’s, because they worry so much about getting good grades that they forget about things that may be more important in life. And really wise people sometimes get C’s. Don’t ever let grades define who you are: you are much more than that.” |

My aim is that decades from now, when students are in the midst of their careers and lives, they will remember an insight they gained from my class that can help them in their understanding. If someone remembers something they learned in my class many years earlier, and uses it to more fully comprehend their lives and world, then my teaching will have been a success. This is why I teach.